When teaching students how to write, and how to improve their writing process, it can be helpful to break written tasks down into six distinct elements:

- Pre-writing, including brainstorming and free writing

- Researching

- Planning, via an outline

- Writing, or drafting

- Revising and reorganizing

- Editing

Not only does it help to break a seemingly gargantuan task into smaller, more manageable tasks, but it also emphasises that different skills are required at different stages to put together a great final product.

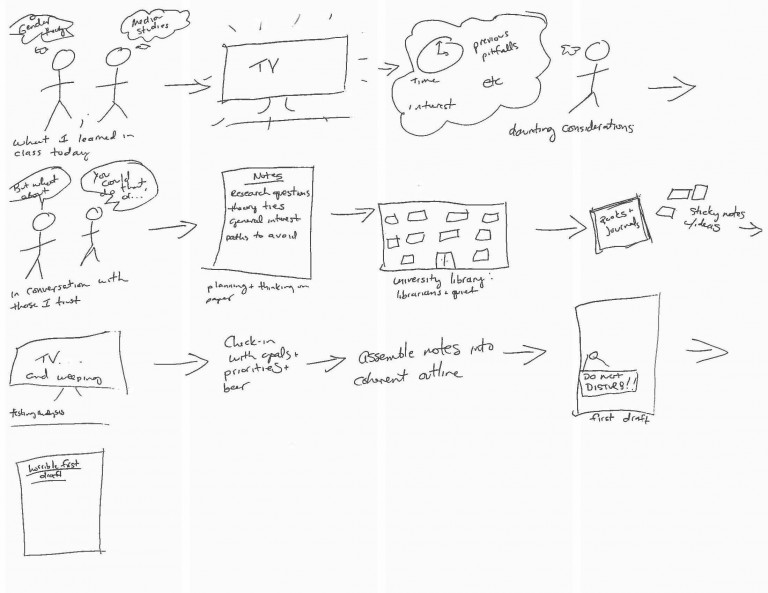

Once students have identified a process that they use, it is useful to have them look and see how well each of the six elements are covered and what approaches work particularly well for them… and which ones simply waste time. An example of such a sketch is shown below:

1) Pre-writing, including brainstorming and free writing

Encourage students to allow some time to think about each and every writing task before they attempt to put pen to paper, or fingers to keyboard. Thinking about a topic and a task is important to allow ideas to develop, but because these ideas will not be fully fledged at this early stage, it is important to draw a visual representation as the process takes shape.

A good method for drawing a visual representation of the brainstorming process is to start by putting the question, or topic of interest at the centre of a page, and then to note ideas, content, and concepts that relate to it further out. Once completed, it can sometimes help to draw a neater version that reorganizes some of the ideas into collective groups.

Some students are reticent to engage with brainstorming if they have tried it before and not found it immediately helpful. You should also offer them the option of free writing, which requires them to set aside a designated period of time (10 – 15 minutes is sufficient for this) in which they just write continuously, without any regard for their grammar or spelling. Similar to brainstorming, this technique can help students to form preliminary ideas about a topic and how they might think about answering a related question.

To get students thinking about their writing process before asking them to start brainstorming or free writing, initiate a class discussion by using questions such as:

- How do you normally start a writing assignment?

- What is the biggest barrier to starting a writing assignment?

- What are your fears when being asked to complete a writing assignment?

- Are there any parts of your writing process you would like to improve?

- How do you start to think about organizing a pieceof writing?

- How do you evaluate each piece of writing you complete?

2) Researching

Most science writing requires students to integrate sources into their work to support any claims they make, but even when that is not the case, it is important to encourage students to spend a good deal of time researching a topic (usually via the scientific literature, held in databases) to build up their content knowledge. Science evolves quickly, too, so students should not rely too heavily on older materials in case understanding or thinking has moved on since they were published.

For more information on researching, and for some top tips on searching the literature, see our downloadable guide here.

3) Planning, via an outline

Whether students are writing lab reports, essays, journalistic pieces or scientific journal articles, it is imperative that they plan what they are going to write before beginning.

Creating a well-defined writing outline will greatly help students to put their thoughts into text in a balanced, logical way, which will make the editing process much smoother. Ultimately, students will save much more time by creating and using a writing outline than by diving straight into a piece of written work.

For more information on creating and using writing outlines, see our dedicated, student-focused resources on this topic, and consider showing the Grammar Squirrel video to help your students visualize how to create their own outline, and to underline why doing so would be a good idea.

4) Writing, or drafting

The important thing to emphasize to students when they reach this point is that they should initially focus on simply getting their thoughts into text, with the help of their outlines, and without worrying too much about grammar or word count. In fact, as long as the students have budgeted enough time/enough time is written into the assignment, a “bad” first draft is not a problem.

The key is to put the main elements together in some sort of logical order to answer the guiding question or meet the goal of the assignment. When they have done this, they have their first drafts. Most students who are relatively new to writing see this as the most important step in the process and believe they should have a finished product at this stage. Offering reassurance that this is not the case will help students more fully embrace writing as a process.

5) Revising, and reorganizing

Most (good) writers compile more than one draft, so it is important to encourage students to read their first drafts critically with a view to making changes or additions to strengthen their arguments, logic, and flow.

However, it is generally a good idea for students to take a break from writing after initially completing their first drafts, so that they can critically appraise these drafts with fresh eyes and minds. Encourage your students to take at least 24 hours off before trying to revise and reorganize their drafts.

If students took the time to think about and produce a well-defined writing outline, they are likely to have less reorganizing to do. However, sometimes it is not clear until reading a piece of work that introducing certain ideas at different stages would strengthen the writing, or that perhaps certain elements require more explanation. Encourage students to restructure their work in such circumstances and produce new drafts.

To help students assess whether their work might need to be reorganized, you can ask them to produce a reverse outline. To do this, ask them to read their piece of writing and list content ideas and the logical development between these in order as they read their work. Once they have completed this, their reverse outline should provide them with a snapshot of the logical flow in their writing. If it doesn’t flow seamlessly, or the content is introduced in a confusing order, a reader (or marker) is likely to find issues with the writing. In these cases, such a reverse outline would indicate where the piece of writing would benefit from reorganizing.

Other options to consider include a peer review component (ask students to swap their papers with their peers and provide feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of these), and/or remind students that they can access tutoring support at their institution’s writing centre.

If you are interested in incorporating a peer review component, see our resources for more tips here and here, and listen to an audio podcast here.

6) Editing

Try to underline that students should not spend time editing their work until they are completely happy with the ordering, logical flow, and content of their final drafts. When they have those higher order concerns in place, it is time to edit for succinctness and grammar, deal with jargon where necessary, and to add effective topic sentences and transitions to make each sentence flow smoothly into the next.

You may wish to direct your students to our helpful resources that focus specifically on editing.

To help students develop an effective writing process, you may wish to give them six mini assignments that will work together to underline the importance of breaking each piece of writing down into the six separate steps from pre-writing, or brainstorming to editing.

* Note that these mini assignments should form small parts of their assessment alongside a more comprehensive writing assignment, where the grading focus should be on the quality of their final piece of writing. For example, if a major part of the assessment is a comprehensive essay, the six mini assignments described below can be deployed alongside this essay to help guide its development. It is best to offer formative feedback as you receive each of the six mini assignments. *

** Also note that full assignment details (and a suggested grading rubric for each one) are only available after you have contacted the ScWRL team to obtain access. Please fill out the Access Request and Feedback Form to inquire about accessing these resources and any others that you are interested in. **

Assignment 1: Pre-Writing, or brainstorming

To get your students thinking about the broader topic around their main assignment, ask them to engage with each other in a brainstorming session to think how they might try to answer the question that forms the basis of that assignment.

When devising the task/question that forms that main assignment, try to choose a prompt that will interest your students, depending on the scientific discipline you are teaching. See our resource on choosing effective writing prompts for ideas.

If your students are relatively inexperienced writers, it could be a good idea to provide a prompt that forces them to consider both sides of an argument, or to justify an opinion with claims, reasons and evidence, because these tasks are generally easier for students to design outlines for.

One example is:

- Imagine that you have discovered how to biologically engineer extinct species and raise them in the lab. Consider the negatives and positives in doing so, and decide whether or not you would bring dinosaurs or other extinct species back to life if you could.

Task (5 marks)

Ask your students to get into groups of three or four and produce detailed visual representations following their brainstorming sessions, which should help them answer the main assignment question. For students that are unsure whether brainstorming will help them, offer them the chance to hand in a piece of free writing based on the same topic/question.

Assignment 2: Researching

Remind students that their work will only be convincing if they are able to justify claims and conclusions by citing relevant literature.

Task (5 marks)

For next class, ask your students to bring an annotated bibliography of as many relevant literature sources as possible that will help them to answer the main assignment question. Encourage them to focus on primary sources and on recent literature. Ask them to bring the full citation details for each source, and to ensure they annotate how they can use each source in their writing.

Assignment 3: Planning, via an outline

Talk to students about producing effective writing outlines (see our dedicated resources for tips, examples and downloadable materials), which should be annotated and coded in relation to their literature sources, so that you can see where they intend to plug information from those sources into the flow of their written work.

Assignment 4: Writing

The key with this mini assignment is to encourage students to produce their first draft long before the date that you ask them to hand in their final piece of writing, so that they have sufficient time to revise and edit it.

Assignment 5: Revising, and reorganizing

You may wish to build in a round of peer review at this stage, so that students can work with -- and obtain feedback from -- their peers. We have produced dedicated resources on integrating peer review into your classes, as well as an audio podcast that provides tips and tricks for building this component into your teaching.

This mini assignment will encourage students to look over their work critically (and to critically listen to peer-review feedback if you integrate this optional component into the process) before highlighting areas of their writing that would benefit from revision or reorganization. It is a good way of ensuring that students don’t just critically assess their own work, or listen to the feedback of their peers, but that they also then take the next step and actually revise or reorganize their work to make it stronger.

Assignment 6: Editing

This final mini assignment will help to encourage students to tighten up their topic sentences, paragraph structure, grammar, use of jargon and general succinctness to make sure their final draft flows smoothly and is easy to read. You may find it useful to refer to our other resources on these topics, or point your students towards them.

The suggested rubric and full task/assignment details require a password for access. We encourage interested instructors to contact Dr. Jackie Stewart and the ScWRL team to obtain access. Please fill out the Access Request and Feedback Form to inquire about resources you are interested in.

Click here for the suggested solutions password protected page